When deploying and operating an OpenStack installation, it is quite natural to discover bugs or features that do not work as one would like them to work. This seems to be a natural entry point to contribute upstream, either by creating a bug report, submitting a patch or discussing some design decision with the developers.

At least this is how it worked for me, then one thing led to another: Once you submit a patch, you’ll see CI results that are triggered by your patch, likely some of these are not passing on the first attempt, so you start looking into what these jobs are actually doing, how to find the logs they generate and how to interpret them.

Contacting the people that operate the CI and discussing possible issues with it happens via IRC. Once you are connected there, you also see what issues other people are having, try to understand what is happening or help them if possible.

In the end this leads to a continous interplay of taking and giving, a community working together for a common goal: Making the OpenStack project a healthy, stable and successful endeavour.

DevStack is a series of extensible scripts used to quickly bring up a complete OpenStack environment based on the latest versions of everything from git master. It is used interactively as a development environment and as the basis for much of the OpenStack project’s functional testing.

https://docs.openstack.org/devstack/latest/

One of the first OpenStack projects that I started contributing to was DevStack. Since for almost all OpenStack repos their functional CI jobs are based on devstack and tempest, this is a crucial piece of code for the whole project, so contributing to keep things in a healthy state is an important task.

The QA team has grown very small over the last five years or so, currently there are only three core reviewers remaining that are regularly active. This is despite the team having been listed in the “help most wanted” list for essentially since it exists https://governance.openstack.org/tc/reference/upstream-investment-opportunities/2023/quality-assurance-developers.html.

Typical contributions include:

Without these, OpenStack development would soon grind to a halt, since lacking a working CI, no further patches could be merged, no releases made and published, no bugs get fixed. So let us take a closer look at how some of the above items work.

The Launchpad site is a complete code hosting and development site, similar to GitHub. It is being developed and operated by Canonical Ltd., the company behind the Ubuntu Linux distribution. OpenStack only uses the bug tracking part of launchpad, which is available at https://bugs.launchpad.net/.

There has also been an attempt from the OpenStack community to develop their own bug tracking software named Storyboard, an instance of this is still running at https://storyboard.openstack.org/. However this never became feature-complete compared to the Launchpad bug tracker, so the migration to storyboard was stopped and a lot of project that had already switched to it have since migrated back to Launchpad.

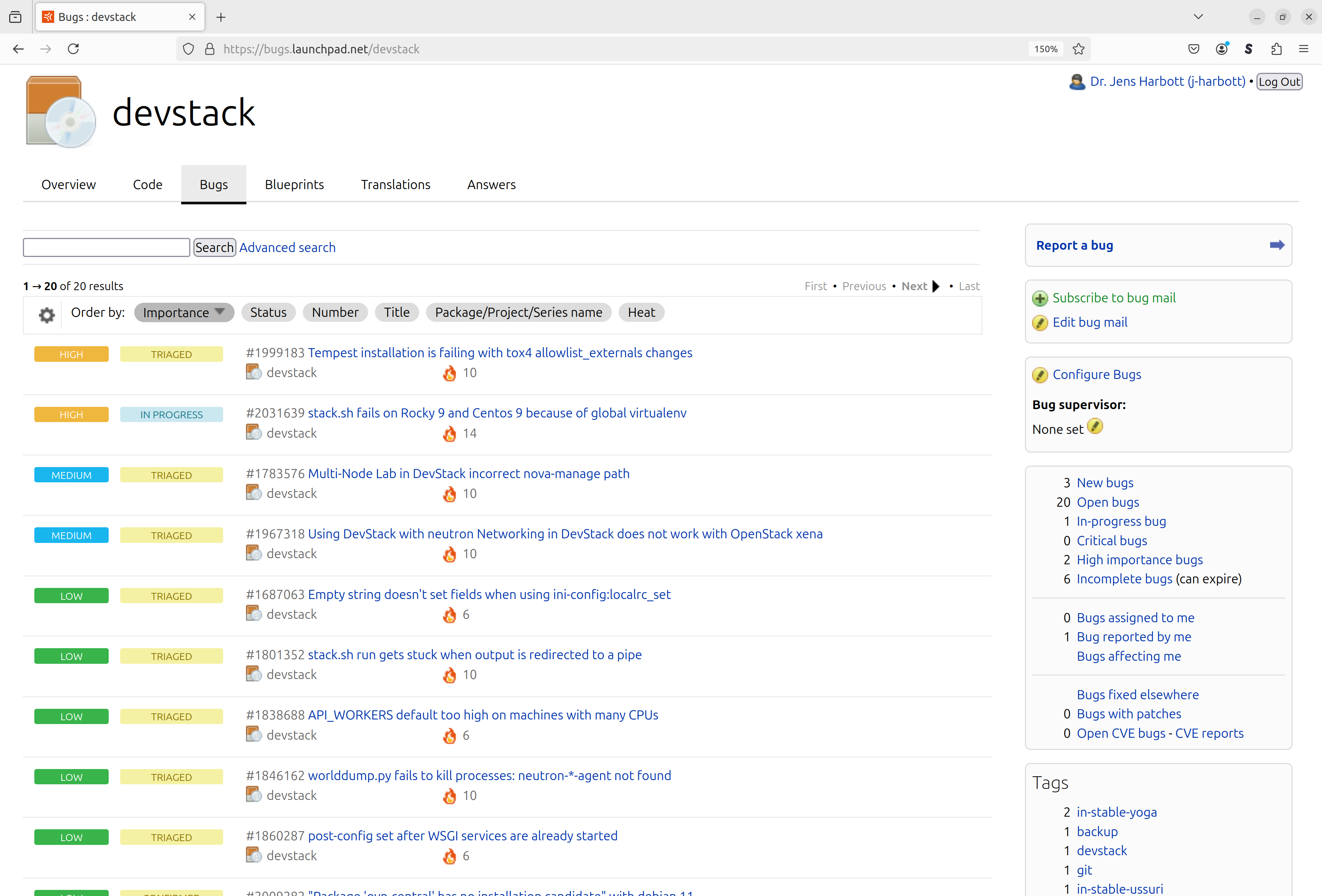

Users that discover a bug within OpenStack can report it at the URL that can be found in the documentation and most of the time matches the project name, for example https://bugs.launchpad.net/devstack.

The landing page shows a list of the open bug reports together with their priority and status, some statistics on the number of open bugs, and finally a “Report a bug” button.

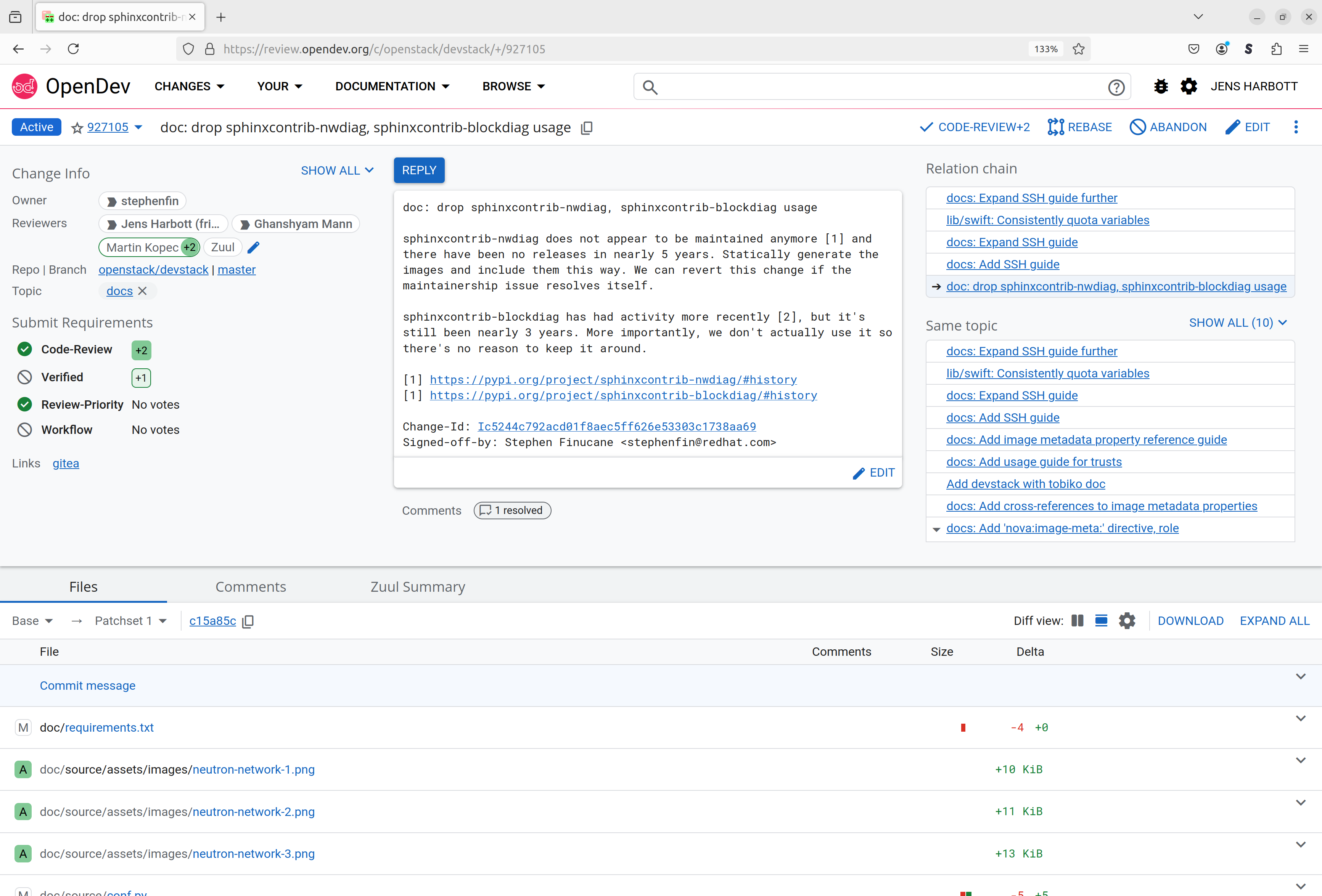

The code review service Gerrit offers a web interface to allow an efficient workflow for reviewing changes (the equivalent of what GitHub users know as pull requests). Take a look at this devstack change for example:

On the left of the upper half of the screen you can see all relevant details about the change, like the Owner, the list of Reviewers and the current status of the review.

The box in the middle shows the commit messsage, which should contain all the information that the author of the patch deems to be important for the reviewer to know and should also contain enough context so that future developer can understand the meaning of the change when looking at it in the git history years into the future.

On the right hand side of the upper half, changes are listed that are somehow related to the current patch. The “Relation chain” lists other commits that were submitted together in a single branch. In GitHub those would all be reviewed in one single piece as a pull request, in Gerrit however each commit is individually tested and reviewed. Gerrit also allows to group reviews together by setting a common topic on them, these reviews are shown in the “Same topic” list.

Below all this, the list of files that are touched by the change is shown. It includes some helpful hints, like an indicator whether a file was newly added (“A”), modified (“M”) or deleted (“D”), and the amount of lines changed (or number of bytes for non-text files).

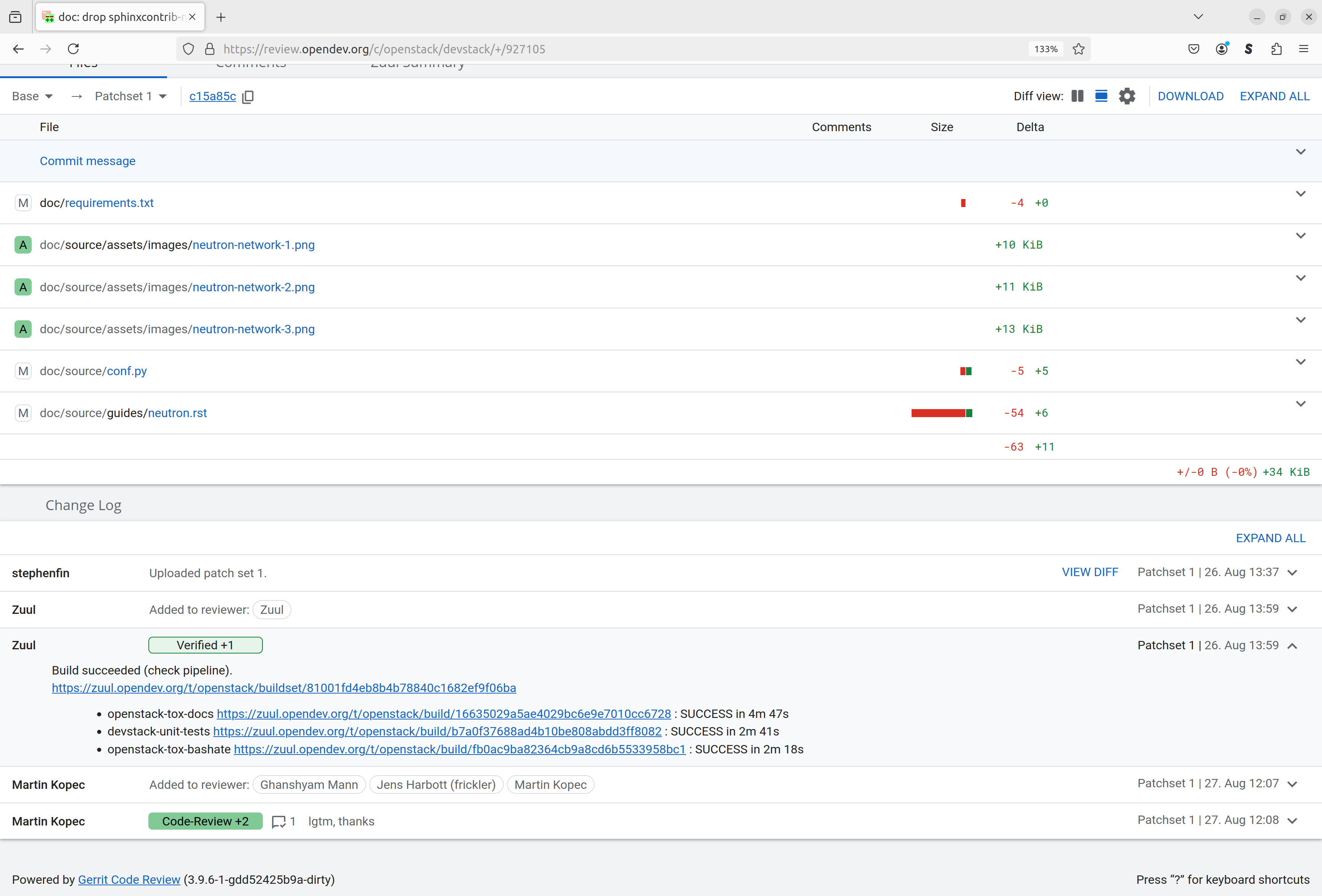

If we scroll further down, the log of events that affect this change is shown. This includes the initial upload of the change for review, test results produced by the CI system (Zuul) and comments from reviewer, including the votes that they left on the change.

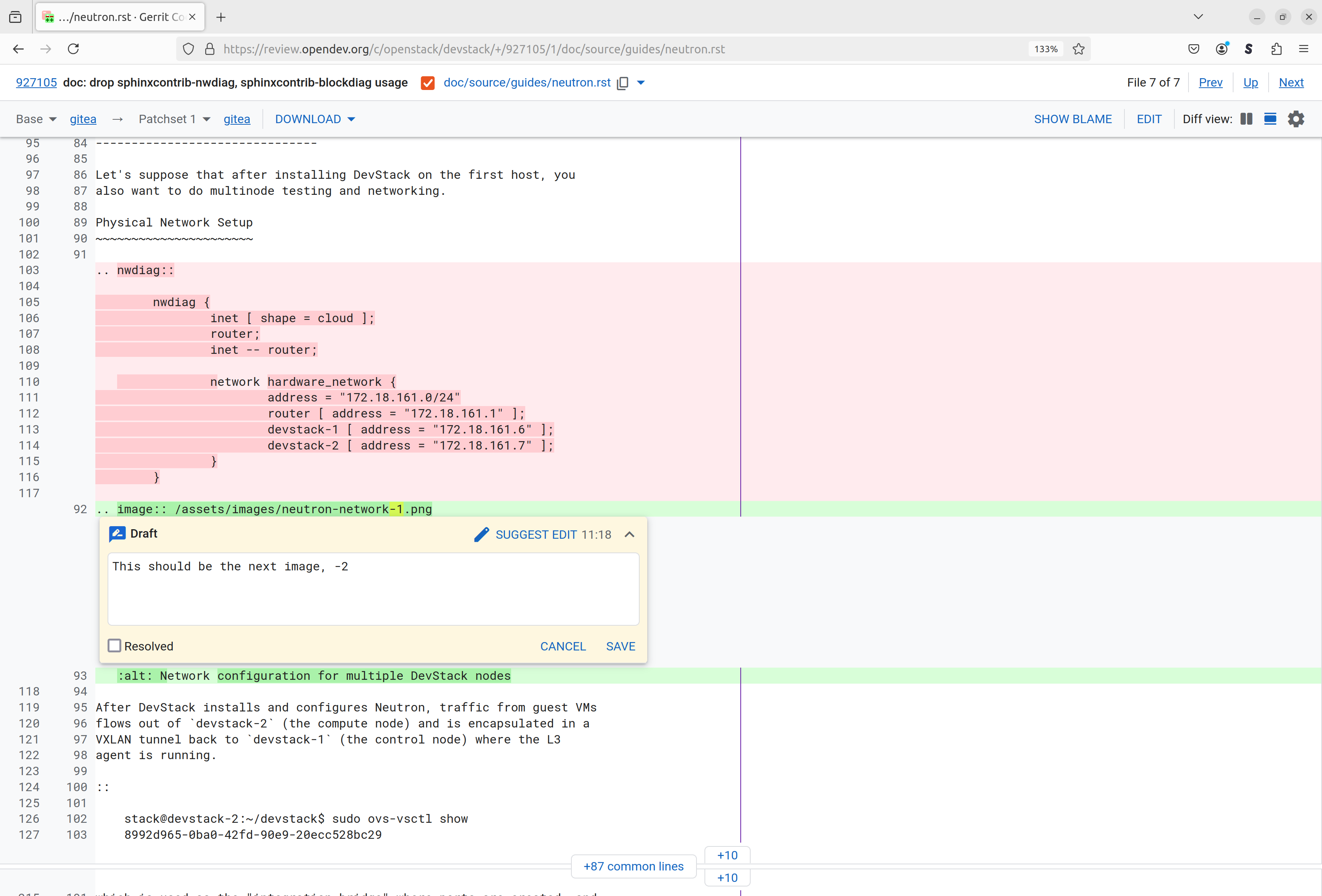

By clicking on a file name, one can take a look at what changed in this file, in this particular case for lines were deleted. Clicking on a line allow to add some comment that will be shown attached to that line and can thus be used to ask the reviewer for explanation in case something is unclear, suggest changes to the commit, or possibly just leave comments for other reviewers.

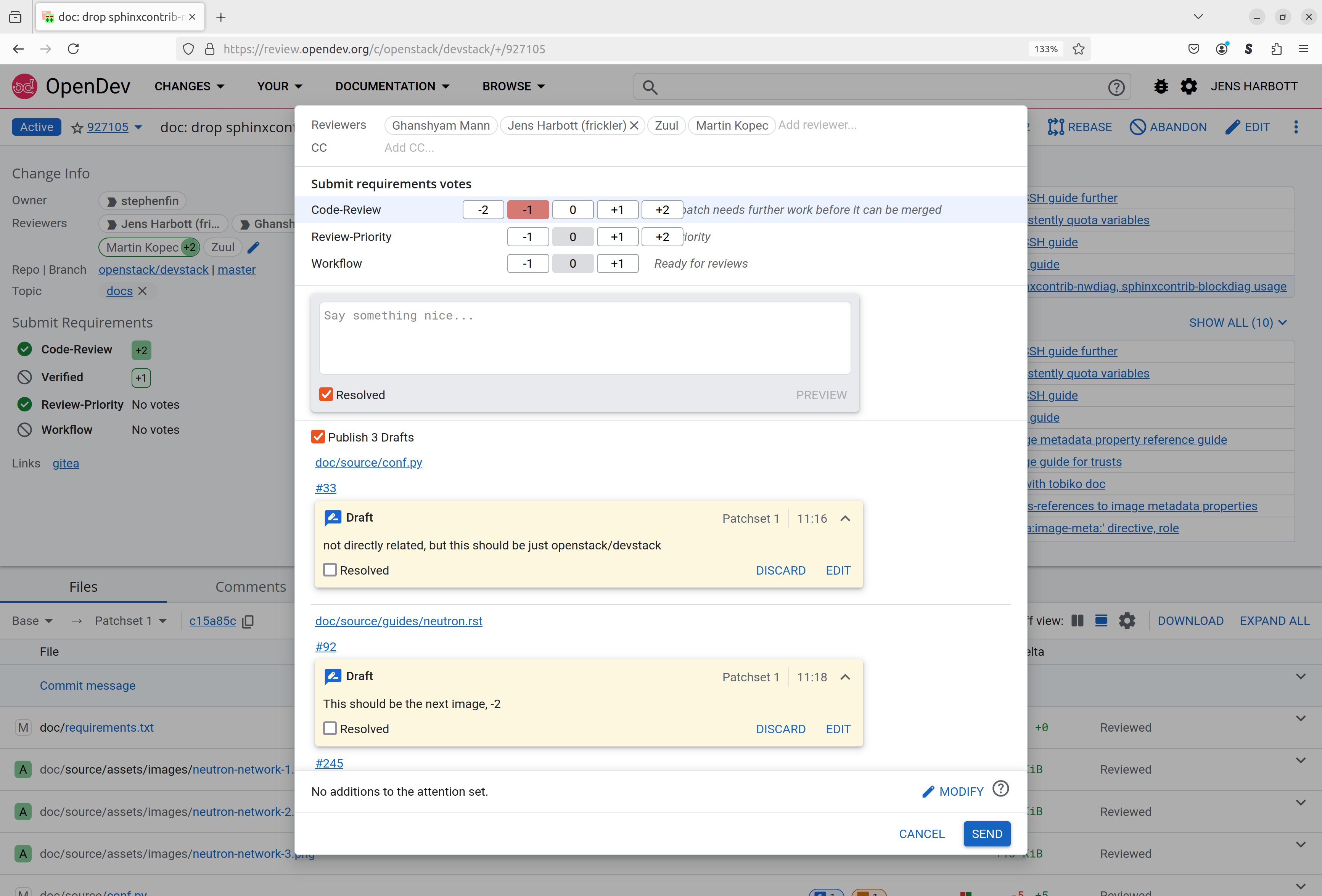

After going through all files, the “Reply” button on the main page will submit the review, adding all the comments together with possibly a vote (-1 in this case since changes to the review are needed).

Most of this can be done by any interested contributor, the only requirement is to register an account, and this is indeed a great option to start interacting with the community, seeing which topics are currently being worked upon, learning about interesting parts of the code and helping to improve the quality of the software that is being produced.

The only part where actual Core-Reviewer rights are needed is when it comes to actually approving a change to be merged into the common code tree. This will usually require two different reviewer to leave a “+2” code review on the patch and then to also submit a “Workflow+1” vote. At this point, the change will still not get merged immediately, but instead the CI will perform another run of jobs, verifying all tests are still passing, and only if these tests are successful, Zuul will instruct Gerrit to actually merge the change.

Keep your builds evergreen by automatically merging changes only if they pass tests

https://zuul-ci.org/

Initially testing the OpenStack project was using existing CI software like Jenkins to run its tests on proposed changes. However a couple of limitations became apparent that in the end led to the development of a new software: Zuul (see https://opensource.com/article/20/2/zuul for some overview of the history)

OpenDev’s instance of Zuul can be found at https://zuul.opendev.org/, it is not only serving OpenStack as one of its tenants, but also the Zuul project itself as well as some other projects.

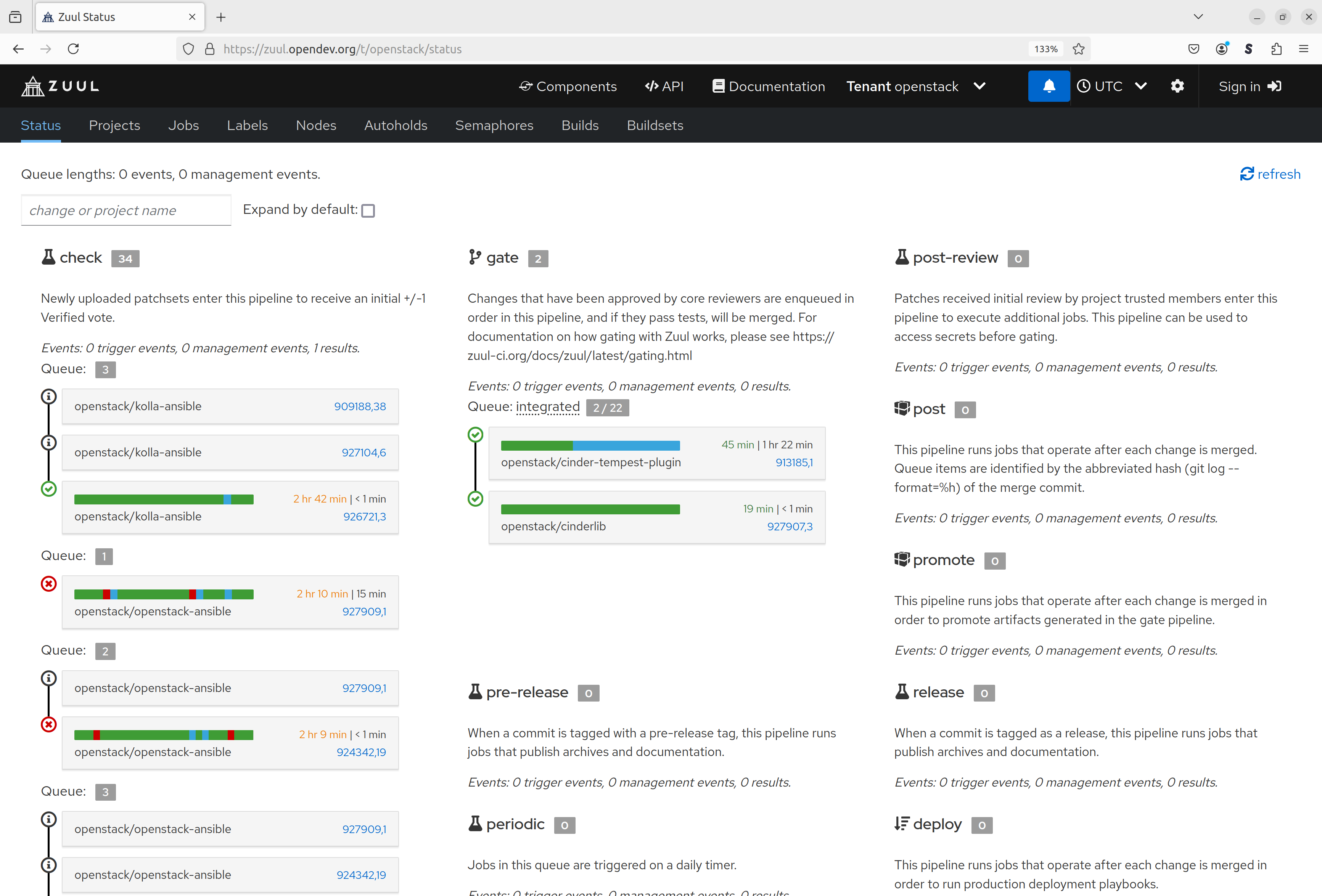

The status page for each tenant shows the current state of the CI: Lists of currently running jobs, grouped by pipeline, together with an estimation of how long it will take for these jobs to finish, based on historical data from previous job executions.

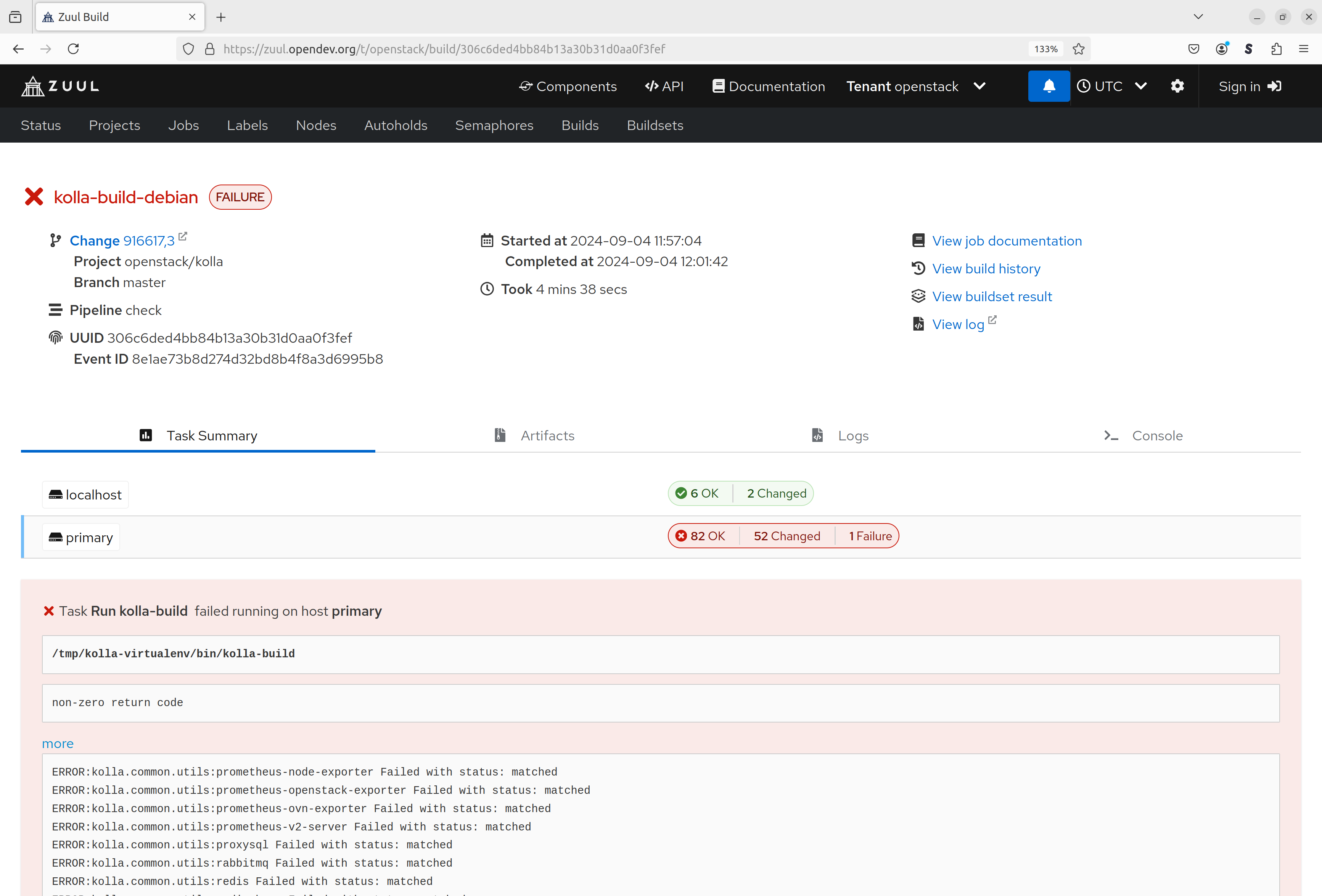

Looking at an individual build allows to see its status and to dig deeper into what went wrong in case there was a failure. One can either follow the sequence of Ansible tasks that were executed in the Console view or check the Logs that were collected.

OpenDev is an evolution of the OpenStack Infrastructure project. The goal is to make OpenStack’s proven software development tools available for projects outside of OpenStack. We believe that Free Software needs Free tools and OpenDev provides one such set that has been proven to work at large and small scales of development.

https://docs.opendev.org/opendev/system-config/latest/project.html

The OpenDev team is operating all - or most of - the infrastructure that is being used in the development of OpenStack. This includes:

Add to that a lot of additional systems that help with development, monitoring and collaboration. Most of the setup is being automated through the “Infrastructure as Code” concept, but since some of the tasks still require administrator or root access to the servers, a good amount of experience with systems administration is needed, as well as having earned the trust of the existing team through previous interactions.

Typical contributions include:

The CirrOS project provides linux disk and kernel/initramfs images. The images are well suited for testing as they are small and boot quickly.

https://github.com/cirros-dev/cirros

The CirrOS project was developed by Scott Moser in order to have a small cloud image for testing purposes, which allows to verify some basic functionality while consuming only a minimal amount of resources. This makes tests work much faster than they would be when using a standard cloud image as provided by the usual distros like Debian or Ubuntu. It also allows the CI to run multiple tests in parallel without hitting resource limits on the testing node.

From time to time updates to the image are necessary, be it either using a newer kernel or an updated software stack - the collection curated by the buildroot project is being used here - or adding new features or bugfixes.

The neutron-dynamic-routing project is a small plugin for Neutron that provides the capability to announce reachability information from OpenStack’s virtual networking to the outside world. One particularly important application of this is to provide IPv6 connectivity with globally reachable addresses to Neutron tenant networks. This has been documented in a detailed guide here.

Due to lack of contributors the project was close to getting abandoned some years ago. But then two contributors from operators stepped up to keep the project alive: Tobias Urdin from Binero and myself. In the last months there has also been some renewed interest from other Neutron contributors and so the project can be considered to be in a healthy state again for now.

Kolla’s mission is to provide production-ready containers and deployment tools for operating OpenStack clouds.

https://docs.openstack.org/kolla/latest/

Kolla is the basis of the OpenStack deployments provided by OSISM. The development follows an “upstream first” policy whereever possible. So every new feature gets implemented in the upstream environment, ensuring compatibility with the current state and thorough testing in the upstream CI, as well as receiving early feedback from other Kolla developers. Larger features usually get discussed with the community even before work on the implementation starts. A good opportunity for this is at the PTG (Projects Team Gathering), which is happening at the beginning of each 6 month development cycle for OpenStack, and which allows to discuss ideas, design choices and possible options in a focused, concentrated enviroment where all interested parties can participate.

The kolla project is using a large set of CI jobs to ensure that all features are working as expected and to prevent changes from introducing regressions. These jobs cover a lot of different deployment scenarios, each of them getting executed for all supported distributions - Debian, Rocky Linux and Ubuntu.

Typical contributions include:

OpenStack is developed and released around 6-month cycles. After the initial release, additional stable point releases will be released in each release series.

https://releases.openstack.org/

The release team is responsible for overseeing the OpenStack release process. This includes verifying the correctness of releases that are being made for individual deliverables, keeping the infrastructure that creates these releases in good shape, and coordinating milestones and deadlines across the wider OpenStack community.

The team is currently very small, not by design, but due to lack of contributors. So being active here has an especially large impact on the healthiness of the whole project. There is some documentation about joining the release team, which describes how interested contributors might start helping out by reviewing release patches.

Reviewing release patches is also the major recurring contribution, particular care is needed in checking that the data are correct and that the reports generated by the CI do not show any possible issues. From time to time, mostly around the major milestones and the final release, the team also generates release patches themselves in order to help the other teams by making their part of the job easier, as they’ll just have to verify that the generated patches are correct.

The OpenStack Technical Committee is the governing body of the OpenStack open source project. It is an elected group that represents the contributors to the project, and has oversight on all technical matters. This includes developers, operators and end users of the software.

https://governance.openstack.org/tc/

The Technical Committee is the central technical governance body overseeing the while OpenStack project. It is responsible for deciding upon the guidelines and policies that ensure that all services can work together in a stable and verified manner. Most actions are getting discussed in the weekly meetings, with longer term strategic planning also happening at the [Project Team Gatherings (PTG)] (https://openinfra.dev/ptg/).